With the emergence of COVID 19 and continued racial discrimination, the fashion industry’s ability to survive is hanging on by a thread. The values the fashion has set are being challenged and the call for inclusivity is slowly rising. With the fast model of fashion, companies and universities must ask themselves if they will make time and devote the resources to work to create new pathways for all. While there is no formula or simple solution for this change, there is one thing that is clear; the way forward starts with a conversation between old and new designers everywhere. With a new generation of consumers on the rise, how will students and professionals work in the industry to break standards that uphold the marginalization of others?

In this quickly changing world, it is hard for those at the top of the ladder to see what is going on at the bottom. As a student, it is also hard to understand what is going on at the top. This creates a gap of knowledge or exchange of ideas from all sides. The trickle-up effect seems to work with trends, but less so with young designers who have suggestions about the structure or learning process for the future of fashion. While coming from the fourth-ranked school in the US for fashion design, I know that my knowledge of the industry still lacks the nuance and experience of professionals. This is a space that I am not alone in, “A four-year degree—or even a two-year degree—can not keep up with the quick rate of change facing most industries…By the time someone graduates, their knowledge is out-of-date,” (Wilkie, 2020). Specifically, students often lack the soft skills that companies require. Often, professors will teach an overall view of the skill, let’s say tech packs or pattern grading, and halfway through will say that students will most likely have to learn it again depending on the company’s system.

Unfortunately, this means that these companies are changing faster than the information that is given to schools as, “adding courses to a degree curriculum, much less restructuring that curriculum, is no small feat. It requires consultation with and approval from many layers of academia. If the college hopes to have a curriculum accredited—something that’s not required but nonetheless coveted in the academic world—the school must jump through several time-consuming, bureaucratic hoops,” (Wilkie, 2020). So even with the hands-on experience of internships that most fashion schools require “a few months of practical experience crammed between classes and other demands is not the same as having a deliberate plan to develop skills over an entire four years,” (Wilkie 2020). COVID-19 has made this especially clear, so how do students still grow with the industry and create innovations in schools that seem to be behind the trends? As students, we come from a unique position as we are not only the future designers but soon the target market of brands as we enter the workforce and have an income of our own. This void leaves room for new discoveries and knowledge that can be shared between both groups.

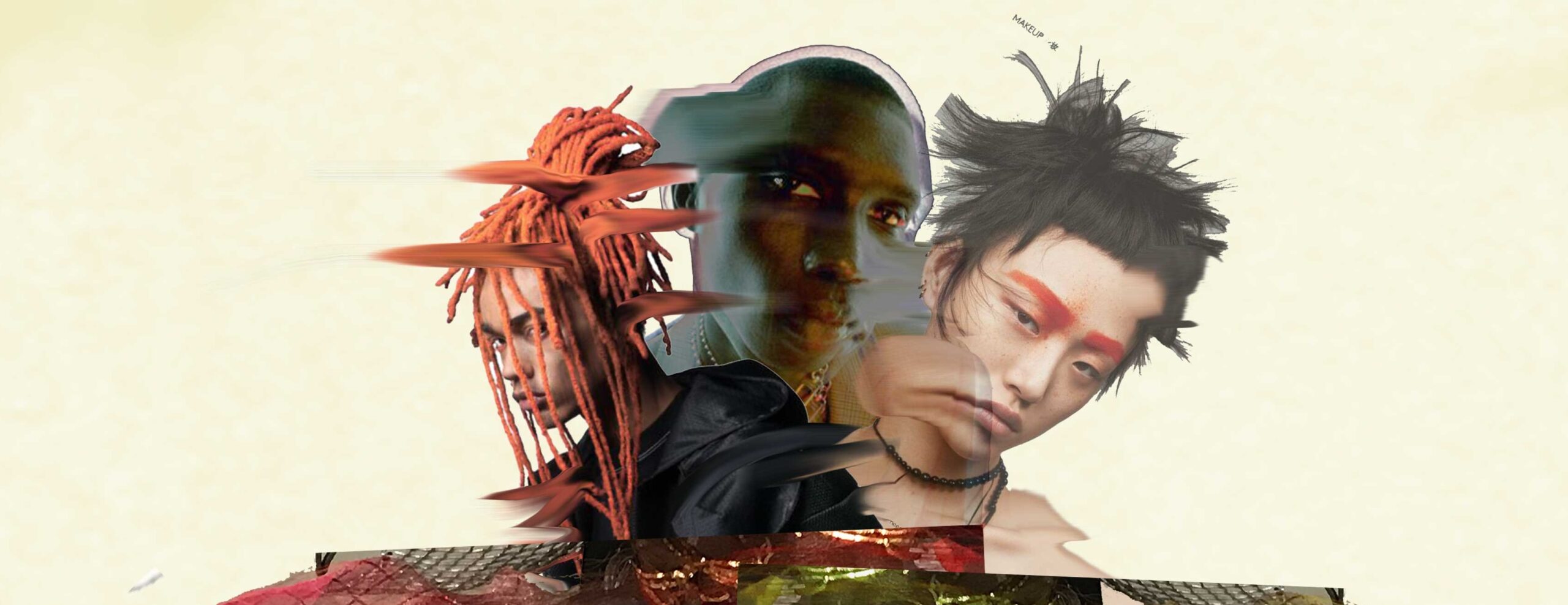

“Unisex” design is one such void that provides many possibilities in the future of fashion. The clothing roles in our lives often affect us in ways we are not even aware of. Societies’ views on gender and the stereotypes it produces have always affected fashion and in term shaped many of our unconscious thoughts. These stereotypes are not new in any form, nor is the thought of a revolution against these ideas. Though the history of fashion (and costume) is far greater than could be covered in this paper and norms have changed over time within different cultures, it remains that they play a role today. The European Institute for Gender Equality’s video on Gender stereotypes and education says, “when we encounter the same stereotypes again and again, they begin to feel natural and shape our preferences and career paths…” (2017). Since fashion plays such an important role in how we live and view our possibilities, it is imperative that not only are all people represented but also able to access clothing that is not based on the 1%. In fact, “Acknowledging gender stereotypes and their consequences is the first step to breaking the mould…” (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2017). Previous icons like David Bowie, Billie Porter, and Prince have cracked the door for generation z by doing just so. The “Statistics show 38 percent of Gen Z-ers ‘strongly agreed’ that gender no longer defines a person as much as it used to, and 27 percent of millennials felt the same way,” and that “These generations are the future of retail, accounting for $143 billion in spending in the next four years,” (Alnuweiri, 2018). The start of a change in fashion is signaled with the addition of a unisex category on CFDA’s website and reflects the shifting priorities of a new generation. In Gucci’s The Future is Fluid, a gen z states “Young people have really utilized social media and the internet to create communities that they might not have instant access to. I have a society at my school and we discuss issues around gender and around sexuality in how the two intersect and how they have repercussions to the individuals and to society…” (2019) Gen z has a strong approach of only supporting brands that align with their core values. With good reason as well, as the echoing thought seems to be that we “Feel like everything could be changed with the move fluid approach to gender because everything is connected, gender influences everything so when you do make a radical enough change it affects politics, how families function, how you go to school, your education system, everything will change.” Nevertheless, exploring these concepts in both school and in the industry is easier said than done.

While gender is becoming more of a “prism of fluidity” for a young generation, the response from the fashion industry is less than perfect and often full of seemingly “positive” steps forward (Gucci, 2019). For most brands, implementing this idea into the regimented standards of fashion has been a challenge. However, we first should look at who has taken steps forward. The Pluid Project is one such brand; they are the first store that has a gender-free layout. This included non-gendered bathrooms as well as an open floor plan. The concept of taking away the specific gendered sections or floors is something that department stores and malls have struggled to grasp. Most stores, however, tout lines that have only a small section within the floors of clothing. They promote these sections with “pinkwashing” to gain social media coverage or a positive image of the band. As many in the fashion field know, the brands use these claims of diversity and inclusivity to boost their sales while not giving back or including those same people in the process. Recently, this has been prominent in promoting diversity, posting messages about Black Lives Matter while not donating or helping the cause with the profits, or continuing to steal BIPOC’s work without credit. The result is lines that look a lot like performative activism. As a young designer, I know that “unisex” design will be looking at similar issues. The possibility for change is there and ready. It is just a matter of collaborating and dedicating time to understand the nuances and intersectionality.

While there are brands specializing in unisex clothing, their price points are unattainable for the average income. In addition, many of the companies that put out clothing that have the unisex label are very masculine in appearance. This clothing is extremely influenced by society’s beliefs and does not take into consideration the need for the prism of identity. There are so many ways to dress but the concept of gendered clothing changes throughout time and societies. One thing is very constant – dressing feminine is always more difficult than dressing masculine and is often met with harsh consequences. That is not to say that dressing masculine also has consequences, but the very idea that there is a masculine and feminine way to dress is a social construct. Designing clothing while not allowing these societal constructs or pressures into the process is something that will require retraining of our unconscious biases. However, the process has begun and with it a new definition that some designers like to use to reimagine the system. The term is genderfluid. It aims to take away the label and judgments of men and women’s clothing to allow the wearer or customer to make their own choice instead of creating a whole new category (as unisex does). This concept allows people to showcase their identity, and as Charles Jeffery states in Vogue, “It’s real – real people, being able to give themselves their own platform to communicate their journeys,” (Anders, W., Bergdorf, M., & Cary, A., 2019).

Furthermore, it is important to recognize how monumental the lgbtq+ community has been in paving the way for unisex and gender fluid clothing and reimagining the system. They are such a huge part of the movement towards a label-free fashion industry and play a role in another important aspect of gender fluid design: pioneering sizing. While most brands continue to keep the same standardized sizing and boxy clothing that was originally created with the male workforce in mind, companies overlook new sizing abilities. In fact, in fashion studies, “no research has examined the consumer population of transgender individuals and their sizing and fit needs relative to clothing. As a result “of the physiological body characteristics distinctive in gender transition (e.g. waist to hip ratio, shoulder breadth) this market demographic likely has unique needs.” (Clothing Fit Issues for Trans People, 2019). The lack of knowledge shows up in schools as well. The Kent State Fashion program does not focus on pattern size grading or how to design for a more accessible future, though they encourage you to do so. For many young designers they must learn on their own. If designers could take away the guesswork and incorporate and learn about these issues it would be the first step to a more inclusive industry.

In light of this I interviewed AJ who is non-binary and Erica who is a trans woman and they shared the problems they themselves had experienced as well as those that they had heard throughout the lgbtq+ community. Out of all the different issues, they agreed that clothing that offered tailored options or more sizing options like stitch fix are the most helpful. For gender fluid design as well, this makes sense. More options means more customers being able to buy clothing. In theory this may mean higher prices but over time the processes and sizing would become standard and require less to produce. This has been shown with how sustainability has become more accessible in the industry as more processes have developed (Piedra, 2018). In addition, more virtual pattern making programs like CLO-3D are emerging that allow young designers to design for different body types and modify patterns easily and more accurately. During the interview I was able to learn more about the common fit issues that they had gathered. Though they were talking about incorporating them in the traditional gendered clothing section, their input is valuable in creating diverse sizing for everyone. They talked about the issues with current menswear, that there could be different crotch lengths, pants for curvy dudes, shorter inseams, smaller mens sizes in clothing and in shoes (down to a size 6 at least), clothes that look good over a binder, tank tops with smaller arm holes, and dress shirts that had smaller shoulders, longer sleeves, and wider torso’s. For womenswear sizing, there could be longer sleeves since they are never long enough, longer torso hem lengths, on dresses with a lower waistline as it is often higher than the natural waist, and shoes that look good scaled larger than a size 10. Men’s clothing shows us that this is possible to achieve; for example, shirts have a collar, body fit (slim, normal, wide), along with many other options for adjustments. The goal, however, is not more men’s and womens’ options but just a wide array of labels based on sizing and not on gender.

These concepts are hardly ever talked about in the classroom. As a design student constantly critiquing or looking at fellow students’ works, I see the disparity in curriculum that is offered to combat the standard fashion has defined. “The result is that most students successfully graduate fashion school without ever attempting to design clothing for a body that isn’t thin, let alone non-binary or disabled.” (Barry, 2020). But it is hard to put all the blame on students, after all, “When students begin their education, the boundaries around what is and what isn’t fashion are quickly and tightly established” (Barry, 2020). At Kent State alone, the electives for fashion have been cut to only two or three options, none of which in the first place focus or devote time to creating clothing for marginalized groups. Teachers often encourage students to design them, but without the school offering “workshops for faculty to unpack and unlearn their own worldviews” or “how to incorporate inclusion into their courses, ”it will continue to be a struggle to design without appropriating or marginalizing further” (Barry, 2020). Though some debate the fashion industry does not work that way therefore schools do not need to put time into developing new courses “The purpose of fashion education isn’t to serve the fashion industry; it’s to lead it,” (Barry, 2020).

The difficulty to break into the fashion industry means that most people must have a degree to enter but when the degree does not prepare or allow students to express themselves, it causes questions for concern. Instead, students and later professionals are faced with the same stereotypes and ideals instead of examining and collaborating to create innovations. This lack of connection between professionals and future designers leaves topics like gender fluid design to be used as another marketing tool instead of a powerful instrument for self-discovery and progression. But gender fluid design and implementation does not have a simple solution. It is not just a matter of changing labels but confronting unconscious biases that we have about gender norms and the intersectionality that race and abled bodies play in them. Understanding how to design for different body types and create customization and different fits is challenging the notion that we need men and women’s sections altogether. Though brands continue to make “unisex” lines that mostly look like menswear; the conversation of gender fluid clothing is not over. The damaging and liberating effect clothing has on people can shape dystopias of new possibilities or continue to put limitations on our futures. Gender fluid labels and brands allowing more expression and the ability to explore clothing without worrying about a designated label on a garment, dismantling the social stigma of worth that clothing has designated for centuries. Though there is no correct starting point, the transference of knowledge is imperative to make sure future generations can continue to create a meaningful difference in fashion.

Bibliography

AJ and Erica Speaker Series 1 [Online interview]. (2020, October 29).

Alnuweiri, T. (2018, November 8). Fashion’s embracing a gender fluid future with unisex collections. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.wellandgood.com/gender-neutral-fashion/amp/

Barry, B. (2020, January 06). Op-Ed: How Fashion Education Prevents Inclusivity.Retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/workplace-talent/op-ed-how-fashion-education-prevents-inclusivity

Clothing Fit Issues for Trans People. (2019). Retrieved November 02, 2020, from https://www.fashionstudies.ca/clothing-fit-issues-for-trans-people

European Institute for Gender Equality. (2017, August 17). Gender stereotypes and education [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrZ21nD9I-0

Gucci. (2019, January 28). The future is fluid [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nFUvLNL7E8Q

Piedra, X. (2018, April 15). What It’s Like to Go Gender-Fluid Clothes Shopping: Liberating, But Pricey. Retrieved November 02, 2020, from https://www.thedailybeast.com/what-its-like-to-go-gender-fluid-clothes-shopping-li berating-but-pricey

Sanders, W., Bergdorf, M., & Cary, A. (2019, August 11). There’s More At Stake With Fashion’s Gender-Fluid Movement Than You Realise. Retrieved October 11,2020, from https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/the-meaning-of-gender-fluid-fashion

Wilkie, D. (2020, February 28). Employers Say College Grads Lack Hard Skills, Too. Retrieved November 01, 2020, from https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/employee-relations/pages/employers-say-college-grads-lack-hard-skills-too.aspx